Hon. Peter Harder moved second reading of Bill S-218, An Act to amend the Constitution Act, 1982 (notwithstanding clause).

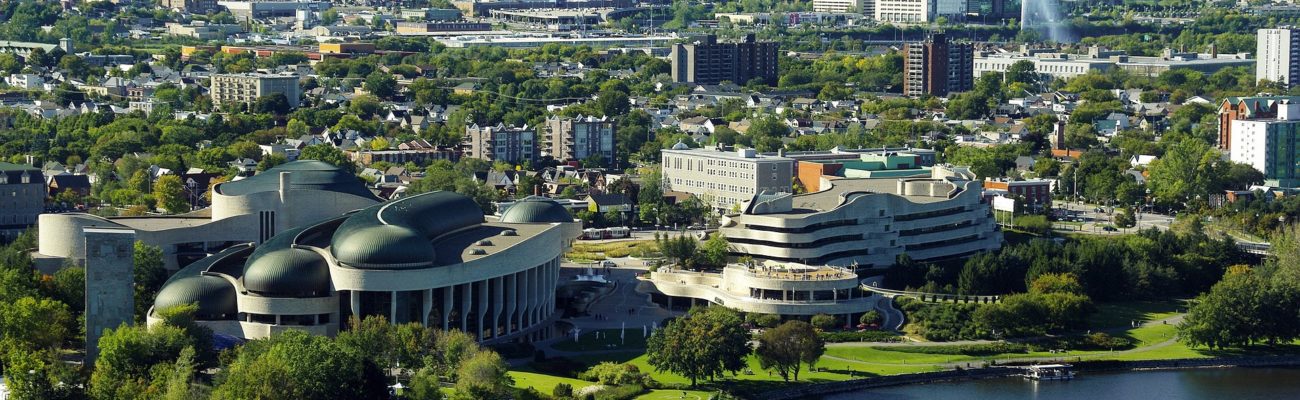

He said: Honourable senators, it is a touch poetic that these walls, once privy to the negotiations to patriate the Canadian Constitution, will once again hear debate to restrict one of the defining compromises that brought that repatriation to life.

This Senate of Canada Building was once the Government Conference Centre, where political stalwarts gathered to discuss a plethora of ideas spearheaded by the federal government of Pierre Elliott Trudeau.

The patriation package, as it is known, transferred the British North America Act, renamed the Constitution Act, 1867 — the nation’s highest law — from the authority of the British Parliament. Beyond removing the grasp of British institutions on our national dealings, the package sought to introduce amendment formulas to alter the Constitution here at home.

No idea was larger or more influential than the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. No compromise was discussed in greater detail than the acceptance of section 33 of the Charter, known as the “notwithstanding” clause.

What was the compromise? The federal government would get their constitutional package, forever changing our rights landscape in Canada, and the provinces — which asked for the “notwithstanding” clause — would ensure their legislative supremacy over the courts when there was seen to be an important conflict of rights.

For the purposes of my remarks, I will use the terms “’notwithstanding’ clause,” “section 33,” and “override” interchangeably.

Prime minister Pierre Trudeau found no joy by including the “notwithstanding” clause and made it clear during and after the patriation of the Charter. Jean Chrétien, Attorney General at the time, wrote in his book My Stories, My Times:

After 1982, whenever I met Pierre Elliot Trudeau, he rarely missed an opportunity to express his frustration at having been forced to accept section 33.

Why was this? Well, Trudeau regretted the Charter was not fully entrenched because governments could still diminish rights by using the “notwithstanding” clause. Yet, it is precisely because of this compromise that we have the Charter today. Those who attended the constitutional discussions agree that without section 33 there would have been no Charter.

Compromise is a cornerstone of a functional democracy. Voters may choose and compromise their choice in elected representatives for what they view to be a greater benefit. Governments may compromise to pass platform commitments, especially minority governments. Even we, as senators, have compromised to move business forward or to simply agree on a committee report. It’s a notifiable way to ensure that viewpoints encompass all that we hear.

But compromise can be tricky, as evidenced by the constitutional negotiations of the early 1980s. It can also be hard work.

It has become apparent to me that, increasingly, populist governments would rather avoid compromise when it comes to the Charter of Rights of Canadians by invoking the “notwithstanding” clause. Oftentimes, it is done pre-emptively, going against all intentions of the provincial representatives who originally fought for it.

This was summed up brilliantly by Thomas Axworthy when he stated:

Today, with polarization and partisanship expanding exponentially, compromise seems to be out of favour when compared to the delights of single-issue fervour.

Politics have turned into a blood sport. The rhetoric and histrionics used by political parties — some more than others — seek to divide and create an “us versus them” mentality. Where the party goes, the base blindly follows, and facts, logic and reason hold no persuasion.

Compromise becomes futile because there is no talking with the perceived enemy. Not everyone encourages or follows this approach, but there’s enough of it to be damaging to our political institutions.

While it has been the provinces which have engaged in what I would call misuses of the “notwithstanding” clause, the then Leader of the Opposition, Pierre Poilievre, not so subtly hinted at its use for certain criminal justice reforms in remarks he gave to the Canadian Police Association, or CPA, in April 2024.

This year, on April 15, during the campaign, Mr. Poilievre went further and explicitly stated a Conservative government’s intention to invoke the “notwithstanding” clause for consecutive sentencing. This is an example of that single-issue fervour noted by Mr. Axworthy.

At the time of the CPA speech, it seemed a Conservative majority government was a sure thing, which surely played into the calculus of the then party leader. The “notwithstanding” clause has never been used federally, and Mr. Poilievre’s announcement worried me a great deal.

The “notwithstanding” clause has lain in abeyance for 43 years, and yet no prime minister has clarified the federal government’s position on its use. It has now taken the threat of a federal provocation for Parliament to wake up and consider how best to deal with such a case should it appear, including us in the Senate. How do we rationalize its use when considering our constitutional duties in this chamber?

Stemming from the motion I introduced last spring, I’ve decided to turn that discussion into action. For those who weren’t here at the time or don’t remember my motion, it called on the Senate to express the view that it should not adopt any bill containing a declaration pursuant to section 33 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, commonly known as the “notwithstanding” clause.

I encourage you to read my speech but, more importantly, those of Senator Ringuette, Senator Cotter and Senator Simons, who also participated in the debate. For what it’s worth, my speech to that motion provides the context as to why I introduced Bill S-218. The wording of the motion was meant to be provocative to inspire discussion and debate. Similarly, you will find that Bill S-218 is equally, if not more, provocative; it seeks to amend our Constitution.

Could this have been a stand-alone bill? Of course it could. However, I didn’t pursue a stand-alone bill for a couple of reasons. First, seeking to alter how the federal government approaches fundamental rights and freedoms in this country — especially ones of this magnitude — should be advanced in an equally serious way.

Second, a constitutional amendment attracts prominence. The point is to be provocative, ensuring robust debate and study on something consequential.

A stand-alone piece of legislation restricting the use of section 33 is constitutional-amendment-adjacent. I want to be direct in stating that the intention is to amend the Constitution, not to appear to be doing so from a distance.

Amending the Constitution isn’t easy because of the constitutional amending formula attributed at the same time as our Charter. However, the amending formula under section 44, dealing with federal, unilateral amendments to the Constitution, may be of service.

Our former colleague Senator Cotter acknowledged this could be the case when speaking to my motion. I would hope that Senator Gold has a similar reading. I look forward to his participation in this debate.

As a reminder to others, the section 44 unilateral amending formula reads as follows, under the heading “Amendments by Parliament”:

Subject to sections 41 and 42 —

— that is, the amendment by unanimous consent formula and the amendment by general procedure —

— Parliament may exclusively make laws amending the Constitution of Canada in relation to the executive government of Canada or the Senate and House of Commons.

This formula is one of the most easily achievable and has been used in the past to increase seats in the House of Commons and to provide representation to Nunavut here in the Senate after its formation in 1999.

Bill S-218 is a more creative use of this amending formula, though one that I believe captures its nature. It does not disturb other amending formulas or the underlying architecture of the Constitution as described by the Supreme Court in its reference on Senate reform in 2014.

This is a relatively simple amendment to a federal use of the section. Bill S-218 is entitled “An Act to amend the Constitution Act, 1982 (notwithstanding clause)” and amends the Constitution to insert section 33.1 after section 33, which deals with the override.

The first provision of this bill, proposed subsection 33.1(1), falls under the heading “Application.” This makes it very clear that the bill affects only the federal Parliament and leaves the provinces out. Provincial inclusion would require a different amending formula with the necessary consultation. That isn’t viable as a Senate public bill. Also, senators may notice that the wording of this provision is taken almost verbatim from paragraph 32(1)(a) of the Charter, which speaks to the application of the Charter as a whole. This ensures continuity with the wording of that proposed subsection while confirming its inapplicability to the provinces.

The next provision, proposed subsection 33.1(2), introduces terminology for the purposes of this bill. The first is “declaration,” referring to a “notwithstanding” clause declaration made under section 33 of the Charter that any act or provision thereof shall operate notwithstanding a provision included in section 2 or sections 7 to 15 of the Charter. These sections pertain to our fundamental freedoms, legal rights and equality rights.

The second term is “infringing bill.” An infringing bill refers to any bill containing a declaration. These terms are found within the bill, and it is helpful to understand their meaning.

Proposed subsection 33.1(3) is simple. It delineates that an infringing bill must be introduced by a minister in the House of Commons. While the government may, in some instances, opt to initiate the legislative process for their bill in the Senate for efficiency or to get a sense of where the Senate is on a particular bill, under this paragraph of Bill S-218, an infringing bill must begin in the House of Commons, much like appropriations and tax bills.

I decided to approach an infringing bill in this way because the current protections built into the Charter of Rights and Freedoms regarding a use of the “notwithstanding” clause and the compromise made between the federal government and the provinces to ensure its patriation require an informed and engaged electorate to keep governments’ feet to the fire. This is found under current subsections 33(3) to 33(5) of the Charter, imposing a five-year sunset clause on a use of the “notwithstanding” clause and a requirement to re-enact a declaration for its continuance. Five years would normally encapsulate an election period, and this would ensure that the electorate had the ability to toss out the government should they discover rights violations stemming from the use of the override to be a final straw.

I argued in my motion speech that I don’t feel this is protection enough against rights violations. It is also for this reason that an infringing bill must begin in the House of Commons with elected representatives. We are not elected and are, therefore, the illegitimate starting point for such a debate.

The next provision deals with prior rulings. This is an exceptionally important part of Bill S-218 because it removes a federal government’s ability to pre-emptively use the “notwithstanding” clause. The pre-emptive use is at the root of recent provincial abuses and has offered telling conclusions as to why it should be removed altogether, federally. The compromise to incorporate the clause in the Charter never included the invocation of the clause prior to the judiciary having their say.

During Doug Ford’s first intended pre-emptive use of the “notwithstanding” clause in 2018, to reduce the size of Toronto’s city council, Jean Chrétien, Roy Romanow and Roy McMurtry came out against its use, saying it was against the spirit of the compromise. That is very important, because they are the three so-called Kitchen Cabinet who thought up the “notwithstanding” clause compromise which made patriation successful.

For the purposes of this bill, there are two avenues ensuring the judiciary has their say. The first is if the Supreme Court has been referred a bill or a provision thereof under section 53 of the Supreme Court Act and has found that bill or provision to be unconstitutional. The second is by the usual process of an outside party challenging the constitutionality of a law or a provision thereof and having it work its way to the Supreme Court as the court of final appeal, which then finds it to be unconstitutional. Either way, unconstitutionality would have to be in relation to section 2 or sections 7 to 15 of the Charter as a proper invocation of section 33 currently dictates.

Should our highest court find unconstitutionality, the minister could then introduce an infringing bill, but the language of the bill would have to match that of the court-tested unconstitutional provisions. If the language changes from that which has already been tested, it could nullify the process of an infringing bill. We all know that language matters when drafting laws.

Further to this, as Sujit Choudhry and George Anderson wrote for a symposium honouring Peter Hogg:

. . . prohibiting the preemptive use . . . increases the political costs and reduces the likelihood of its use by forcing a government to confront a judgment finding a law unconstitutional. . . .

It adds to proper discourse between the courts and the executive and legislative branches, as originally intended.

The next four provisions of Bill S-218 attempt to guarantee there is proper public disclosure and awareness as to what the rights violations are and the government’s rationale for pursuing a “notwithstanding” override with an infringing bill. The first includes a preamble within an infringing bill incorporating the reasons for the declaration. Preambles are common course in legislative drafting.

The next provision, proposed subsection 33.1(6), requires that a Charter statement be tabled with the infringing bill speaking to the potential effects on rights under section 2 and sections 7 to 15, along with the reasons why an infringement of those rights can’t be justified using section 1 of the Charter alone. This proposed section allows governments to infringe Charter rights subject to reasonable limits prescribed by law. The government must detail why it chose to invoke the “notwithstanding” clause rather than utilize the well-known test for complying with section 1.

As stated by Senator Cotter during his speech last Halloween, the “notwithstanding” clause:

. . . pre-emptively delegitimizes many rights and, implicitly, the value of section 1 — the rights-limiting clause — and the jurisprudence of the Supreme Court of Canada in crafting a sophisticated approach to section 1.

The government should have to explain its position in advance.

The subsequent provision falls under the heading of “Time allocation.” Simply, it removes the ability to curtail debate on an infringing bill. It applies to both the House of Commons and the Senate. This is vital to ensuring that such important matters be considered fully before any potential vote occurs.

Proposed subsection 33.1(8) of Bill S-218 is similar to that of the previous provision but relates to Committees of the Whole in both chambers. Should an infringing bill receive a positive vote moving it to committee stage, a Committee of the Whole cannot be used to expedite study. Committee study is the most important work MPs and senators undertake, and it is where in-depth analysis takes place and expert opinions are heard. We use the information to supplement our thinking as lawmakers and offer potential solutions or compromises. Eliminating the committee process on such a fundamental issue as Charter rights is neglectful and uncaring, especially for minority populations who are most frequently at the wrong end of rights abuses.

I hope these four provisions will work to better inform Canadians of legislation that fundamentally affects their constitutional rights so that the so-called five-year sunset already found within the Charter can operate as intended. The “notwithstanding” clause is meant to check the courts, and the people are meant to check the government, but what checks an uninformed populace? If Canadians aren’t aware that their rights are being abused, the five-year sunset clause is impotent. Populist governments will take the easy path to achieve their ends, as we have seen provincially. Guardrails are needed.

The final provision would change voting requirements in the House of Commons. Under this proposal, any motion to read an infringing bill for a third time will require a supermajority of 66% of votes in the House from the entire membership. That is 227 votes in favour out of 343. Further, should a majority government have more than 227 seats, there is a requirement that another recognized party support the infringing bill.

This would only apply to the House of Commons, not the Senate. The elected chamber should have the weightier decision-making duty. The Senate will contemplate the same in due course but with consideration to the decision of the elected chamber. This is an accountability and transparency measure that I hope the chamber would agree with.

Make no mistake, these proposed amendments intend to make a federal invocation of section 33 more difficult but not impossible. I believe these amendments run parallel to the original intentions of the drafters of this clause more than four decades ago. In 2025, this is more important than ever. Today, Canadians often don’t understand Charter rights or what they mean, and they are largely ignorant of the “notwithstanding” clause. This can be explained by the simple passage of time as well as the clause’s relative disuse until 2018. But it’s also because of the way many Canadians receive information and distrust institutions and authority figures generally. Properly informing Canadians of their rights and what an override may do to them is the very purpose of this bill.

Let’s remove the shortcuts, slow down the process and ensure that Canadians know what’s at stake before there’s a federal abuse of section 33. This is why a full judicial appeal process must be standard before the introduction of an infringing bill and why unfettered debate should be encouraged. If a government wants to override our rights, it should explain itself by meeting these criteria.

Colleagues, these conditions are not all my own. I spoke to the Peter Lougheed principles during my motion speech. Lougheed, the premier of Alberta at the time of the constitutional negotiations, along with Sterling Lyon of Manitoba and Allan Blakeney of Saskatchewan were adamant defenders of the idea of the “notwithstanding” clause.

Lougheed spoke to the “notwithstanding” clause and its inclusion in the Charter at the University of Calgary during a very famous lecture in 1991. I wish to quote from it where he said:

The purpose of the override is to provide an opportunity for the responsible and accountable public discussion of rights issues, and this might be undermined if legislators are free to use the override without open discussion and deliberation of the specifics of its use. There is little room to doubt that, when defying the Supreme Court, as well as overriding a pronounced right, a legislature should consider the importance of the right involved, the objective of the stricken legislation, the availability of other, less intrusive, means of reaching the same policy objective, and a host of other issues. It should not . . . be the responsibility of the Courts [said Lougheed] to determine whether a limit is reasonable or demonstrably justifiable in a free and democratic society. . . .

Having witnessed the uses of the “notwithstanding” clause in Quebec which applied it writ large to their laws in protest of being the only province not to sign the Charter, and in Saskatchewan which used it pre-emptively in a labour relations bill, Lougheed concluded that the original purpose of the clause wasn’t being respected nor was it providing an opportunity for responsible and accountable public discussion of rights issues.

After nine years of thinking about the “notwithstanding” clause, Lougheed — in this very same lecture — proposed three amendments to the section.

The first is that Parliament or a legislature be required to spell out the purpose of any legislation disallowing standard form overrides of rights. This was a proposal from the 1985 Royal Commission on the Economic Union and Development Prospects for Canada, also known as the Macdonald royal commission. The commission’s recommendation reads as follows:

The Charter’s general override provision should contribute to public awareness of legislation limiting the constitutional rights of citizens in Canada.

Overriding legislation should include a declaration of intent to legislate, notwithstanding a provision of the Charter, and should include not only reference to the specific rights being overridden, but also an indication of the purpose of such legislative action.

Such a statement would help the courts to ensure that limitations do not exceed what is necessary to achieve the objective; it could also be a useful reference point in discussions on whether to extend the override after the five-year period.

This approach is covered to some extent in Bill S-218.

The second Lougheed amendment would require a supermajority of 60%. He argues that invoking the “notwithstanding” clause is too substantive an action by the elected body and requires a higher level of authorization than a simple majority. This is consistent with a 1991 proposal paper offered by the Government of Canada, entitled “Shaping Canada’s Future Together,” which proposed a 60% supermajority. I agree and I have insisted instead on a two-thirds majority consisting of two recognized parties, ensuring dialogue and compromise.

Lougheed’s last amendment proposal ensures the “notwithstanding” clause is never invoked pre-emptively.

He states:

In my mind, such an action is undemocratic in that the purpose of section 33 was ultimate supremacy of Parliament over the judiciary not domination over or exclusion of the judiciary’s role in interpreting the relevant sections of the Charter of Rights.

He anticipated that all rights of appeal be exhausted before an invocation, which you will find under the “Prior ruling” subheading in Bill S-218, though I have proposed that a reference to the Supreme Court would also be action-provoking.

I have tried to incorporate Lougheed’s principles into my own bill because I believe, as he did, that they are pragmatic amendments preventing the abusive nature of section 33.

Some of Canada’s major law associations have also called for versions of Lougheed’s proposal to safeguard or limit the use of the “notwithstanding” clause. In a letter entitled “Establishing Guidelines Concerning Use of the Notwithstanding Clause” to then-Minister of Justice and Attorney General Arif Virani, the Canadian Bar Association proposed four guidelines which include: barring the pre-emptive use of section 33; requiring a two-thirds majority vote in a legislature or Parliament; a requirement of meaningful and transparent public consultation before invocation; and preambular statements as to why it has been considered necessary to invoke the clause.

These proposed guidelines are all found within Bill S-218.

In December 2024, the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, or CCLA, also wrote to then-Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in a letter entitled “Misuses of the Notwithstanding Clause Are a Threat to Our Charter.” The CCLA recommends three limitations, two of which we know well: disallowing pre-emptive use of the clause and a supermajority requirement when voting. This builds on their Save Our Charter campaign, which can be found on their website, and it speaks to the damages of recent uses at the provincial level.

The third limitation in their letter would allow courts to review uses of the “notwithstanding” clause. This, in my opinion, may be a bridge too far considering the original purpose of the inclusion of section 33 by the provinces. If public consultation is part and parcel of the “notwithstanding” clause process, this should suffice in allaying fears of its misuse. Put another way, if the populace is determined to be the final arbiter of rights issues, let them be informed of the trade-offs before the federal executive can ascertain the ability to invoke.

A question can be asked here: How is it possible to legislate these guidelines when we are not able to legislate in a restrictive way for future governments? I would say that there is a difference between legislating substantive issues and legislating procedural requirements. Bill S-218 does the latter; it places self-imposed procedural restraints on the enactment of federal bills invoking the “notwithstanding” clause. These are also known as manner and form requirements.

Professor Craig Scott from Osgoode Hall Law School stated manner and form requirements are the following:

. . . statutory requirements that one legislature seeks to impose on future legislatures in the form of either inhibitory preconditions or facilitative permissions for the enactment, amendment or repeal of statutes or provisions within statutes. . . .

The manner and form requirement of Bill S-218 would be an inhibitory precondition for the enactment of laws containing the “notwithstanding” clause.

While Bill S-218 legislates in a restrictive way by implementing a manner and form requirement, it does not withhold the ability of federal governments to invoke the “notwithstanding” clause, nor are these amendments immune from repeal. They would be difficult to repeal, however, based on these grounds and on what is being protected. One of Canada’s foremost constitutional experts the late Peter Hogg was confident that manner-and-form amendments are appropriate in Canada’s legal structure.

Coming from his authoritative constitutional text Constitutional Law of Canada, he wrote:

While a legislative body is not bound by self-imposed restraints as to the content, substance or policy of its enactments, it is reasonably clear that a legislative body may be bound by self-imposed procedural (or manner and form) restraints on its enactments.

He then wrote:

Would the Parliament or a Legislature be bound by self-imposed rules as to the “manner and form” in which statutes were to be enacted? The answer, in my view, is yes.

If Bill S-218 makes its way through Parliament to receive Royal Assent, it would be a self-imposed law: Parliament would have agreed to the restrictions it is placing on itself.

Manner-and-form restrictions aren’t without precedent. For example, provinces abolished their upper houses using ordinary legislation, making them unicameral. This is manner-and-form legislation. Parliament or legislatures could add other elements to their legislative processes for all laws, or for particular kinds, as long as their ability to do so isn’t usurped by a constitutional amending formula. Yes, I am using a constitutional amending formula, but the federal unilateral amending formula — not one that requires consultations and the amending formula involving provincial governments.

While this bill seeks to make legislating the use of the “notwithstanding” clause more onerous, both Peter Hogg and Craig Scott bring up the example from Westminster, which used manner-and-form requirements to make legislating easier. The British Parliament Act, 1911, was enacted by the House of Commons and the House of Lords. It provided that a bill could be become an act of Parliament without the consent of the Lords if it were passed by the Commons and rejected by the Lords in three consecutive sessions of Parliament over a period of not less than two years.

The Commons then used this manner-and-form procedure in 1949, without consent of the Lords, to add further leniency to the same provisions, increasing the power of the Commons by delaying the Lords’ delaying power to two sessions and one year.

The manner-and-form requirement initially established with the Lords was subsequently used against them.

Hogg indicates in his manner-and-form chapter in Constitutional Law of Canada that in order for a manner-and-form provision to be fully effective in law it must also apply to itself. This is called being “doubly entrenched” or “self-referencing.” Essentially, manner and form must not only apply to the protected category of laws — in this case, federal laws that invoke the “notwithstanding” clause — but it must also apply to laws that seek to amend or repeal the manner-and-form provision itself. If we were to follow his recommendation, the criteria I have provided allowing for an invocation of the “notwithstanding” clause would also apply to amendments to, or the repealing of, this bill. I decided against the double entrenching of this provision, and I am glad to see Senator Gold nodding in approval.

The fact that a constitutional amendment is being sought should be enough to deter future governments from trying to repeal it altogether. It wouldn’t be a winning strategy to attempt to reduce those rights we are trying to protect through the outright repeal of Bill S-218.

It is by amending the Constitution that the manner-and-form requirements gain credence. In amending the Constitution for these purposes, it, too, will form part of our supreme law.

A standalone bill attempting to do the same wouldn’t have the same gravitas or deter abuses. It’s another reason why I felt it appropriate to amend the Constitution itself rather than taking an outside-looking-in method of a standalone bill.

Taking the arduous path here is the right approach. It displays the federal government’s leadership and the importance it places on protecting fundamental rights. If the federal government implements restrictions on the use of the override through a constitutional amendment, perhaps the provinces will be inspired to do the same. My hope is that provinces will see the benefits of being self-limiting and reduce the tyranny of the majority in its use.

An argument could be made that the “notwithstanding” clause has fallen into disuse since it has not been used federally in 43 years. As a result, restricting its use is easier for the federal government than for the provinces.

As such, a constitutional convention of disuse may now exist. This is an opinion also shared by Senator Cotter, who, in the same speech I referenced earlier, said:

. . . we have matured as a nation . . . with the assistance of the Supreme Court of Canada and its own articulation of rights and their limitations. We have matured in our understanding of basic rights and their boundaries to the extent that parliamentary interference to negate those rights is no longer needed — hence a convention, at least with respect to Parliament, that the notwithstanding clause is inoperative.

He goes on to say that this maturation:

. . . has taken us to a place where as citizens, we recognize as a matter of principle that it is no longer wise to preserve parliamentary supremacy in ways that can deny . . . human rights. . . .

He continues:

. . . we are in a new era in which the preservation of certain rights, those captured in the Charter, adequately defined and circumscribed, ought not to be exposed to the vagaries of parliamentary supremacy.

This was my thought process when first hearing the then-Leader of the Opposition imply his intended use of the “notwithstanding” clause. But this begs the questions: What if provinces continue to disobey the spirit of the 1982 compromise by continuing use of the clause? When does the federal government step in or do they at all?

An employable tool remains in place for the federal government: disallowance. Found in section 90 of our Constitution, disallowance would essentially allow federal cabinet to remove provincial laws from the books.

The last use of the disallowance power came in 1943, so it can be argued that a constitutional convention exists in its disuse as well.

If a perpetuation of rights violations exists provincially, could we see a federal government blow the dust off this provision? It would likely cause joint crises in constitutionalism and federalism and likely wouldn’t be worth the political costs, so calm down. A convention of disuse of section 33 federally, and a convention of disuse of disallowance should be respected. Two wrongs don’t make a right.

I introduced Bill S-218 with the original drafters of the “notwithstanding” clause in mind, and their commitment to compromise. This bill itself is a compromise: while I’d rather see it completely removed, I am proposing safeguards instead. They don’t block its use, and they don’t disrespect parliamentary supremacy. They do, however, restrict its use federally by ensuring that proper conversations occur to inform Canadians, the ultimate arbiters of rights, where their rights stand.

While Mr. Poilievre initially hinted at the use of the clause to the CPA, he removed subtlety altogether during the election campaign by stating that he would impose the “notwithstanding” clause for consecutive sentencing. This is perhaps a not-so-shocking appeal, but keep in mind that this is the first time it has been promised federally.

To borrow an analogy from Benjamin Perrin, Prime Minister Harper’s former legal adviser, the “notwithstanding” clause is part of the Charter like an:

. . . emergency-exit door is part of an airplane: you’d better have a very good reason to use it and be prepared to explain yourself if you do so.

I note that the use of the clause was nowhere in the written Conservative Party platform. This tells me that Mr. Poilievre cares more about politics than the Constitution, and that an abuse of power is worth reaching for as a means to a political end.

He’s also following the provincial movement by attempting to equate democratic legitimacy with rights abuses.

The democratic legitimacy approach is a weak argument, especially when the necessary public discourse is all but avoided. Perhaps more disturbing is that the Conservative Party seemingly supports such an abuse of power overall, as Mr. Poilievre’s remarks speak to larger capital-C Conservative policy on justice reforms.

While an immediate threat of the use of section 33 federally has subsided in the recent election, I would argue that ensuring restrictions prior to a future threat is even more necessary in this Parliament. Political winds shift, and we must be prepared.

I ask that we move this bill to committee for study, where we can call upon experts who are eager to participate.

Rights determinations were always envisaged to be a dialogue between governments and the courts after the courts have spoken. Removing the courts reduces rights to a monologue — an elected, majoritarian soliloquy. It is time to insist on constitutional supremacy.

Thank you.